Extraits / Excerpts

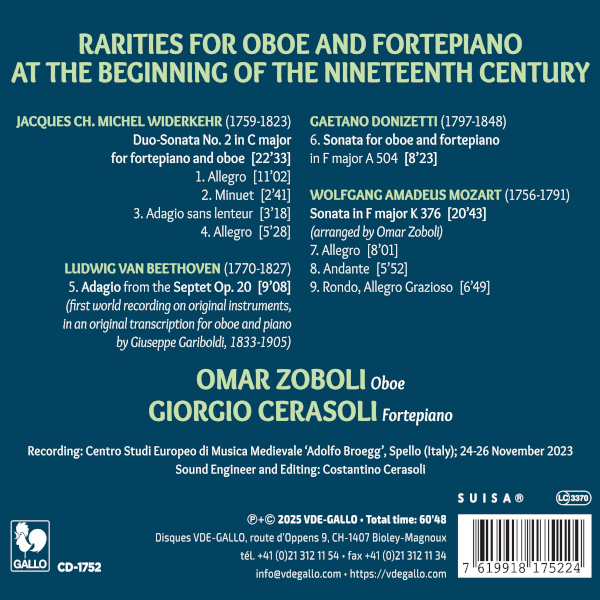

Widerkehr: Duo Sonata No. 2 in C Major - Beethoven: Septet, Op. 20: Adagio - Donizetti: Oboe Sonata in F Major - Mozart: Sonata in F Major, K. 376 - Omar Zoboli, Oboe - Giorgio Cerasoli, Fortepiano

Jacques WIDERKEHR: Duo Sonata No. 2 in C Major: I. Allegro – II. Minuet – III. Adagio sans lenteur – IV. Allegro – Ludwig van BEETHOVEN: Septet in E-Flat Major, Op. 20: II. Adagio cantabile (Arr. for Oboe and Piano By Giuseppe Gariboldi) – Gaetano DONIZETTI: Oboe Sonata in F Major, A 504 – Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART: Violin Sonata in F Major, K. 376 (Arr. for Oboe By Omar Zoboli): I. Allegro – II. Andante – III. Rondo, Allegro Grazioso.

Omar Zoboli, Oboe https://www.omarzoboli.ch/

Giorgio Cerasoli, Fortepiano

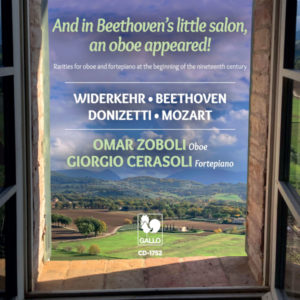

And an oboe appeared in Beethoven’s parlor

Did the oboe really make an appearance in Beethoven’s drawing room? It certainly regularly entered the rooms where the German musician created his compositions. Ludwig van Beethoven, in addition to reserving for the reed instrument a prominent place in his orchestral works (it would suffice to recall the solos at the beginning of the Funeral March, in the Eroica Symphony, and at the reprise of the first half of the famous Fifth Symphony), wanted it among the protagonists in several of his chamber compositions: from the Quintet for piano and wind instruments to the Trio op. 87 (where two oboes converse with an English horn), and the extraordinary Octet Op. 103. Probably for both the aforementioned Trio Op. 87 and the Variations on a Theme from Mozart’s “Don Giovanni” WoO 28 Beethoven had in mind the brothers Johann, Franz and Philipp Teimer, celebrated Bohemian performers whose long activity came to an end in 1796, the year in which Johann and Franz, almost certainly the oboists in the trio, died.

Chamber music in the domestic salon

But let us return to the drawing room to recall how chamber music production was designed—still in Beethoven’s time—predominantly for domestic performances, precisely in those drawing rooms of the aristocracy and upper middle class that, throughout Europe, hosted performances reserved for residents and their guests. For theaters and concert halls, in fact, programs intended for orchestral ensembles were basically reserved. The repertoire that circulated in European salons, clearly different depending on whether one was, for example, in Vienna, Paris or Bohemia, was extraordinarily broad. With the possibility therefore of encountering a vast array of composers who are less well known today but who drew on the same musical language used by the most celebrated musicians, namely Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven.

Let a gastronomic comparison be illuminating: the wealth of ingredients used was entirely shared by a large number of cooks, each of whom then developed recipes according to his or her own taste and inventiveness. That is why even the works of musicians such as, for example, Jacques Christian Michel Widerkehr (1759–1823), to whom we shall return later, Friedrich Theodor Fröhlich (1803–1836) or Carl Anton Philipp Braun (1788–1835) not infrequently contain passages, harmonic solutions, stylistic traits that may be recognizable to those familiar with the classical style of the better-known triad. At that point it is not a question of finding out who copied and who was copied, because each artist had as a reference the same musical vocabulary used not only by Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven but also by many other colleagues.

Widerkehr and echoes of Beethoven

It will come as no surprise, then, that the same first two harmonies with which Beethoven’s First Symphony opens are found at the beginning of the second of Jacques Widerkehr’s Trois Duos pour piano et violon ou hautbois, composed around 1794 and published by Érard in 1817. Born in Strasbourg, possibly a pupil of Franz Xavier Richter, the Frenchman, thanks to his cello studies, played regularly in Paris from 1783 with the Orchestra of the Olympic Lodge and that of the Spiritual Concerts but without being permanently on the staff. His main activities, until the Revolution, therefore seem to be music teaching and composition. It is the fashion for concertante symphonies that allows Widerkehr to know celebrity: during the Revolution and the Consulate his name appears frequently in concert programs.

The solo parts of many of the pieces of which he is the author are written first and foremost for wind instruments (clarinet, flute, oboe, bassoon or horn) and are intended for the early musicians of Paris. Like these concertante symphonies, considered among the best in circulation at the time throughout Europe, his chamber music reveals a luminous style, accurate in detail and rich in the combination of harmonic effects. These characteristics are also found in the Deuxième Duo pour piano et violon ou hautbois, in C major and articulated in four movements, where the classical sonata generally contains only three: two allegros (the first of which is in sonata form and the second en rondeau) frame a brilliant minuet, by then very close to the scherzo found in symphonies, and then a slow movement, particularly expressive.

Arrangements and accessibility in the 19th century

Still throughout the 19th century, listening to music in the drawing rooms of the wealthy classes also meant listening to pieces transcribed for a different ensemble than originally intended. In the absence of the means of reproduction that had in fact only arrived in the twentieth century (from gramophone to vinyl, from radio to CD), in order to listen to music it was necessary for someone to physically perform it. And since at least the second half of the eighteenth century, publishing had been working to provide professionals and amateurs with a wide variety of options for adapting music written for larger or simply different ensembles to the limited resources available in a home. Thus Beethoven’s string quartets also became available in transcriptions for four-hand piano, his Symphonies in transcriptions for piano and a few other instruments, and so on.

Gariboldi’s transcription of Beethoven’s Septet

Prominent among these ‘adaptations’ is one made by an Italian musician whose name let it be clear is not the result of a misprint: Giuseppe Gariboldi. A native of Macerata, born in 1830 and died in 1905, he was a renowned flutist as well as a composer and conductor. He lived and worked mainly abroad, especially in Paris, where he served as a flute teacher. For this instrument, in addition to a large number of original compositions, he transcribed one of Beethoven’s most intense pages, namely the Adagio from the famous Septet. Gariboldi reduces the ensemble of Op. 20 (clarinet, horn, bassoon, violin, viola, cello, double bass) to only two performers: accompanied by the piano is a flute (replaceable, as in our case, by an oboe), which is in fact entrusted with the main melodic lines that in the original are the responsibility of the clarinet. The smaller number of performers involved does not seem to harm the expressiveness of this movement at all; on the contrary, the resulting timbral result is very interesting: indeed, it is the case that the oboe makes an unexpected but surprising appearance in Beethoven’s drawing room.

Donizetti and the oboe as prima donna

Gaetano Donizetti’s extensive non-theater production—a production including symphonies, quartets, quintets and several pages for piano and solo instrument—also includes a Suonata for oboe and piano, the date of composition of which is not certain while the date of publication is, which occurred as recently as 1966 thanks to the publisher Peters. If the Bergamasque composer’s interest in the quartet form, a real test-bed during the musical training he had first with Giovanni Simone Mayr and later at the school of Father Stanislao Mattei, reveals his attention to the instrumental production of the great transalpine composers, this Suonata seems to clearly meet the tastes of an audience for whom vocal music was of primary importance. A light guise, just two movements (Andante – Allegro), for a composition that is anything but uninventive, given the grace and expressiveness Donizetti achieves in this fresco with a clearly theatrical flavor. And, while remaining a chamber, hence salon context, it is evident that especially in the Andante that opens the work the oboe behaves exactly as if it were a prima donna on the stage of those theaters for which the Italian musician produced his best-known works.

Mozart’s Harmoniemusik and salon transcriptions

The primary role played by the oboe in the output of another great of classicism, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, is beyond dispute, not only because of the mass of Divertimenti and Cassazioni that were part of the tradition of the so-called Harmoniemusik (i.e., music for ensembles of wind instruments only) but also such gems as the Quintet for Piano and Winds K. 452 and the Concerto for Oboe in C major, later transcribed for flute and transposed to D major (this version, K. 314, allows one to trace directly back to the lost original for oboe).

In the case of the Sonata K. 376, it can be said that the oboe enters the Salzburg composer’s musical salon by passing through a side corridor: the piece by Mozart intended in the original for violin and piano is in fact offered here in an arrangement for oboe of a transcription for flute from the early 19th century. In fact, the substitution of violin for flute or, in this case, oboe, does not entail significant changes, leaving the qualities of this page unaltered. Third in a group of sonatas published by the publisher Artaria in 1781 under the title of Six Sonates pour le Clavecin ou Pianoforte, avec l’accompagnement d’un Violon, it presents the same richness of ideas, brilliance and intensity that characterizes the entire collection. Mozart can be said to achieve an ambitious goal here in the balance between the two instruments, finally overcoming the dominance of the keyboard instrument. So much so even at the time the need for a violinist as skilled as the pianist was noted.

Period instruments and expressive fidelity

Last but not least, it is worth mentioning the instruments used for this recording: these are a classical oboe, a copy of a two-key instrument by Heinrich Grenser dating from around 1810, and a fortepiano, a copy of an instrument made by Anton Walter in 1795. Although the period between the last decades of the 18th century and the first decades of the next sees both instruments undergoing constant change, the distance separating them from their corresponding modern instruments remains enormous. The timbral characteristics of these two period instruments seem to combine with each other in an ideal way, directly influencing their phrasing and, ultimately, the very perception of the score.

Above all, one understands the intimate relationship between the music and the instruments for which it was conceived, exploited to the fullest extent of their possibilities, sometimes even taken to the limit of these possibilities to create effects of particular expressiveness. A situation that gives credit not only to the scores of the best-known composers but also to those of many other composers, seemingly secondary but equally decisive in exploring all the possibilities of the classical musical language.

Giorgio Cerasoli

- Categories

- Composers

- Interprets

- Booklet