Extraits / Excerpts

Bach: Passacaglia and Fugue in C Minor, BWV 582 - Two Chorals, BWV 650 & BWV 740 - Concerto in A Major, BWV 1065 - Pastorale in F Major, BWV 590 - Guy Bovet

Johann Sebastian BACH: Passacaglia and Fugue in C Minor, BWV 582: I. Passacaglia – II. Fugue – Kommst du nun Jesu vom Himmel herunter, BWV 650 – Wir glauben all’ an einen Gott, BWV 740 – Concerto for 4 Harpsichord in A Minor, BWV 1065: I. Allegro (Transcr. For Organ) – II. Largo (Transcr. For Organ) – III. Allegro (Transcr. For Organ) – Pastorale in F Major, BWV 590: I. Siciliana – II. Allemande – III. Aria – IV. Gigue

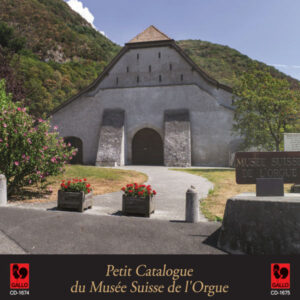

Guy Bovet aux orgues de l’Abbatiale de Romainmôtier. https://www.guybovet.org/

The Works

The Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor, BWV 582, is without doubt one of the master’s most famous works; one of those which poses the most interesting problems of registration for the organist; which enables him also, more than a normal prelude and fugue, to demonstrate the different ‘timbres’ of the organ— which was in this case a determining factor in the choice of the work. On a bass, unremittingly repeated (sometimes varied and moving freely to other voices of the counterpoint, but always present) variations unfold, each one more astonishing than the other. Chords, arpeggios, counterpoint—all the styles are used and just when every possibility seems exhausted, then there begins a fugue in triple counterpoint (that is to say that the theme is always accompanied by two countersubjects, which can be placed as desired in the order of the voices) a fugue which again pushes back the limits of fantasy, enriching the theme with its new elements. It culminates in a spectacular ‘Napolitaine VIth’ chord, to end in a majestic peroration.

Chorale: Kommst du nun Jesu vom Himmel herunter (BWV 650). This is the last piece in the Schubler chorales collection, who edited it during Bach’s lifetime. This collection is also called ‘Transcribed chorales’—in effect, they are parts of cantatas which Bach has transcribed for the organ, no doubt because of their popularity. In the original of this one, the garlands of the right hand are entrusted to a solo violin, the chorale to the tenor solo, a bass continuo accompanying it all.

Chorale: Wir glauben all’ an einen Gott (BWV 740). This is the decorated version, with double pedal, a marvel in miniature. A four voice accompaniment (two on the manual, two on the pedal), is made marvellously transparent by the use of different stops for each pair of voices, which allows the statement of the theme to be heard often before the soprano entry, and supports a discreetly ornate melody, which suddenly flies away on the final chord.

Pastorale (BWV 590). This is one of Bach’s less played pieces—and wrongly so. Perhaps because of the almost total absence of a pedal part (why shouldn’t the music be beautiful all the same); perhaps also because one cannot here create a big noise. It is nevertheless full of charm and is a composition that owes nothing to the ‘great organ’ works of the Cantor. The first section, obviously inspired by the Italian Pastorales, themselves in the musical style of the Roman ‘pifferari’, enables us to hear a duet of bagpipes with a bourdon fixing the harmony. Afterwards comes a kind of Allemande in C major, followed by a cantilena on the chalumean in subtle chromatic passages. The work finishes on a two-part fugato which could symbolise the rings of the Christmas angels.

Concerto (BWV 1065). This is not one of the concertos transcribed directly for the organ, but a transcription of a transcription. In effect, originally in B minor for four violins and orchestra, it was arranged by Bach for four harpsichords and orchestra. It is from this version that I have made the organ arrangement, using the methods which Bach himself employed when he arranged the concertos for a single keyboard instrument. The work certainly loses the solo parts, which are no longer four but one or two at most, but it gains in transparency. In any case, try to separate out the sounds of four violins or four harpsichords playing at the same time.

The Organ of Romainmôtier

Built by the firm of Neidhardt & Lhöte of Saint-Martin (NE), and completed in 1972, the organ is certainly one of the most interesting instruments of our period to be built in Europe. It is distinguished by its extreme sobriety, the quite firm intention to not ‘play everything’, from which comes its originality; in fact, it is perfectly possible to play almost everything on it. The generous acoustics of the church, of course, play no small part in this, rounding the angles where necessary and providing an ideal sounding box for the instrument. The construction is oriented primarily towards the music of southern Europe, with ranks of ‘Ripieno’ in the Great Organ and ‘Flauto in Ottava’ for the evocation of Italy; for Spain, warm and mysterious colours and ‘anches en chamades’; and for the music of France, all the detailed stops as well as the benefit of a majestic ‘Grand Plein Jeu’ and an excellent ‘Grand Jeu’.

Why then play Bach on it? It may in fact seem rather odd to choose precisely this organ to record music for which it is certainly not easy to obtain a balanced registration; music which demands an organ of a rather decadent nature, where the stops mix well, not having too much personality; an instrument which does not intrude and which submissively performs all the musical demands of the organist. The organ of Romainmôtier is exactly the opposite of this—a pure-bred stallion—rearing willingly, it must be kept on a very tight rein to enable a preconceived idea to be imposed. But these are the organist’s problems, and the public, listening to its marvelous sounds, need not be concerned. When these problems are considered from the angle of the organ, its richness and sobriety, they really cease to exist, and new perspectives are revealed for even the most well-known pieces. One must work with and not against the instrument, allowing it to guide and inspire.

It is in this spirit that we have worked with this organ; also in this spirit, the repertory has been chosen, a large part of which is nevertheless inspired by the sunny music of Italy. We have handled the organ of Romainmôtier with economy, never pulling or pushing more than one stop at a time, based on the principle that ‘what the organ does not want to do, it must not be made to do’. Although for this recording we benefited from the presence of a capable assistant, all the stop changes performed in the pieces played could be done by the organist alone, without any help.

Guy Bovet

| Timbres | Registres |

|---|---|

| Grand-Orgue (II) | Montre 16, Montre 8, Prestant, Doublette, Quinte 1 1/3, Petite Doublette 1, Fourniture 4 r, Cymbale 4 r, Flûte 4 |

| Positif (I) | Flûte à chem. 8, Prestant, Nazard, Doublette, Tierce, Fourniture 3-4 r, Cromorne, Tremblant doux |

| Trompettes (III) | Trompette, Clairon, Cornet 5 r, Basse de Clairon en Chamade, Dessus de Trompette en Chamade, Dulzaina 8 horizontale |

| Echo (IV) | Bourdon 8, Flûte à chem. 4, Flûte 2, Tierce, Sifflet, Voix humaine, Tremblant fort |

| Pédale | Flûte bouchée 16, Flûte 8, Prestant 4, Fourniture 3 r, Bombarde, Trompette, Clairon, Petit Clairon 2 |

- Categories

- Composers

- Interprets

- Booklet