Extraits / Excerpts

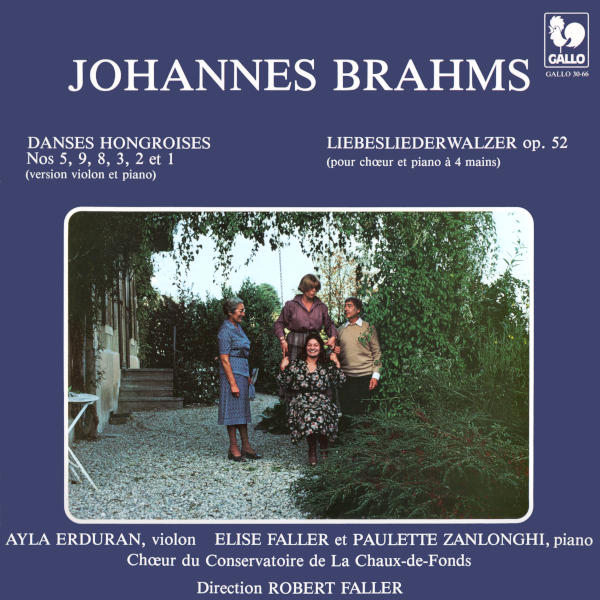

Brahms: Liebesliederwalzer, Op. 52 - Hungarian Dances, WoO 1 - Ayla Erduran, Paulette Zanlonghi, Elise Faller, Chœur du Conservatoire de La Chaux-de-Fonds, Robert Faller

Johannes BRAHMS:

21 Hungarian Dances, WoO 1: No. 5 in G Minor – No. 9 in E Minor – No. 8 in A Minor – No. 3 in F Major – No. 2 in D Minor – No. 1 in G Minor.

Liebesliederwalzer, Op. 52: No. 1, Rede, Mädchen, allzu liebes – No. 2, Am Gesteine rauscht die Flut – No. 3, O die Frauen – No. 4, Wie des Abends schöne Röthe – No. 5, Die grüne Hopfenranke – No. 6, Ein kleiner, hübscher Vogel – No. 7, Wohl schön bewandt – No. 8, Wenn so lind dein Augen mir – No. 9, Am Donaustrande – No. 10, O wie sanft die Quelle – No. 11, Nein, est ist nicht auszukommen – No. 12, Schlosser auf, und mache Schlösser – No. 13, Vögelein durchrauscht die Luft – No. 14, Sieh, wie ist die Welle klar – No. 15, Nachtigall, sie singt so schön – No. 16, Ein dunkeler Schacht ist Liebe – No. 17, Nicht wandle, mein Licht – No. 18, Es bebet das Gesträuche.

Ayla Erduran, Violin (Wikipedia)

Paulette Zanlonghi & Elise Faller, Piano

Chœur du Conservatoire de La Chaux-de-Fonds, Robert Faller, Conductor (Wikipedia)

Johannes BRAHMS (1833–1897)

Love-Lieder Waltzes and Hungarian Dances — two aspects of ‘Music for the Home’

Piano for four hands is closely linked to the development of the two works recorded on this record. In fact, the Hungarian Dances, numbering 21, were first written for piano for four hands and the original title of the waltzes is: Love-Lieder waltzes for piano for two hands (and song ad libitum).

Is it, here, a question of a production for four hands? The parenthesis and the mention of ad libitum would seem to relegate the vocal portion to the background. In point of fact, however, both in the spirit of the work and in Brahms’ intention, such was not the case.

For him, the Love-Lieder waltzes are not to be changed and executed without the song parts, unless a perfect balance could be maintained by certain changes which would give a satisfactory rendering, independent of the voices. This version, without voices — another concession to the editor but also, it must be stated, responding to Brahms’ own interest — actually exists as Opus 52a.

Two questions arise here: firstly, in what way could music for piano for four hands be in the main assured of a wide distribution? Secondly, apart from material considerations, what would the musical possibilities of piano for four hands represent for Brahms himself?

The appearance of the lower middle class and middle class among music-lovers after 1800, the development of the piano industry, the integration of ‘piano lessons’ as part of the education of young girls of quality, brought music into the home circle. The piano for four hands was the privileged make-up of the ‘Music for the Home’. The success and the extension of this method of practising music guaranteed a constant flow of pieces written for this type of training.

The success of Opus 52 and, in particular, of the Hungarian Dances, whose first collection of ten dances appeared during the same year (1869), brought renown to Brahms after the 1870s and made him a world-famous composer. During the subsequent ten years after their appearance, their success inspired the author, spontaneously or not, to arrange them for piano for four hands, and for two hands also, then to orchestrate them and even to create ‘new’ Love-Lieder waltzes, Opus 65.

In 1870, it was the orchestration of eight waltzes of Opus 52, and of one of Opus 65 (which, in fact, was not yet published); in 1872, the transcription of the first ten Hungarian Dances for piano for two hands; in 1873, the orchestration of three of them; in 1874, the Love-Lieder waltzes for piano for four hands, Op. 52a, which we have already mentioned; in 1875, the New Love-Lieder waltzes for four voices and piano for four hands, Op. 65; in 1877, the New Love-Lieder waltzes for piano for four hands, Op. 65a; in 1880, the second collection of Hungarian Dances (Nos. 11–21) for piano for four hands. The least that one can say of Brahms is that he certainly knew very well how to develop his success.

It is no exaggeration to say that, at the present time, the Hungarian Dances are the most popular of Brahms’ works. Those which were not yet orchestrated by their author have been by other hands. Others have been arranged for different formations. We owe to Joachim those for violin and piano, recorded here.

It is well said that they were and are always popular and not merely known. The dances have penetrated right into circles normally closed to music. The distribution by records of their orchestration, embellishing and varying the colouring of the Hungarian themes and the seductive and exotic Slav rhythm, are the cause of this. But, we would add, a potential popularity was already intrinsically woven into their original version for piano for four hands.

The piano, also, and above all because two persons can play it together, opened up the way to music for the 19th-century middle classes, and the latter, in return, were able to absorb a large part of the romantic productions for piano for four hands more easily — this being said without any judgment of value.

The whole of Brahms’ compositions for four hands, with one possible exception, the Variations on a Theme of Robert Schumann, Op. 23, are moreover classified among entertainment music: besides the Hungarian Dances, there are 16 Waltzes, Op. 39, and the Love-Lieder waltzes, Op. 52a and Op. 65a.

The Love-Lieder waltzes, Op. 52, for piano and song, which it was Brahms’ wish to see spread among all circles where ‘Music for the Home’ was cultivated, are also entertainment music.

Nevertheless, Brahms is the very symbol of serious music, respecting traditional forms and highest aspirations. The lower classes of society, which made their irruption at the beginning of the last century into musical life, gave rise to the elaboration of a music whose character and style were destined more and more to become separate and distinct from so-called serious music, known as hereditary and conservative of the classical century of aristocratic music.

Serious music and entertainment (light) music — between these two types and in this new social situation, the romantic composer finds himself in a contradiction. On the one hand, he is called upon to create a unique work, a work of genius which is the fruit of an inspiration devoid of all material consideration. On the other hand, the ‘democratisation’ of music obliges him to be constantly conquering his public. There are no more kings or princes who receive and pay regularly for his services. The composer has to sell his music, and the pieces of ‘Music for the Home’ are his means of keeping in close contact with his public.

This does not mean that the romantic composers, when writing light music for entertainment, did so without genius or against their will. The Love-Lieder waltzes and the Hungarian Dances are probably the most typical fruits of the ‘romantic’ contradiction in which Brahms, in common with his contemporaries, found himself.

François Brun

- Categories

- Composers

- Interprets

- Booklet