Extraits / Excerpts

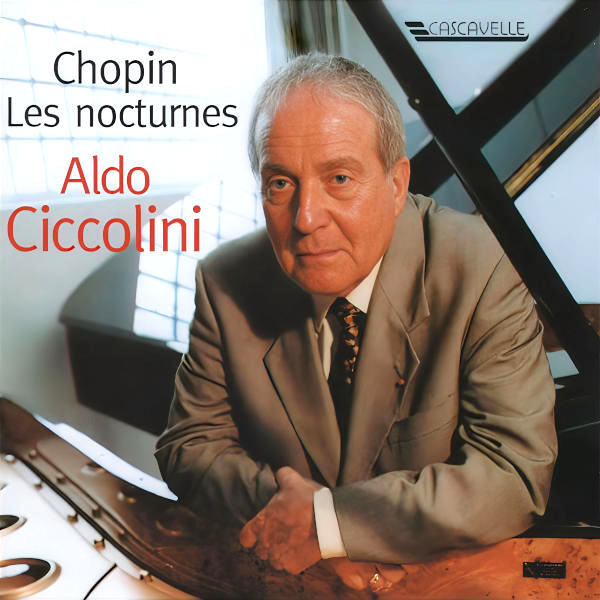

Chopin: The Nocturnes - Aldo Ciccolini

Chopin: The Nocturnes – Aldo Ciccolini

CD1:

Frédéric CHOPIN: Nocturne No. 1 in B-Flat Major, Op. 9, No. 1: Larghetto – Nocturne No. 2 in E-Flat Major, Op. 9, No. 2: Andante – Nocturne No. 3 in B Major, Op. 9, No. 3: Allegretto – Nocturne No. 4 in F Major, Op. 15, No. 1: Andante cantabile – Nocturne No. 5 in F-Sharp Major, Op. 15, No. 2: Larghetto – Nocturne No. 6 in G Minor, Op. 15, No. 3: Lento – Nocturne No. 7 in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 27, No. 1: Larghetto – Nocturne No. 8 in D-Flat Major, Op. 27, No. 2: Lento sostenuto – Nocturne No. 9 in B Major, Op. 32, No. 1: Andante sostenuto – Nocturne No. 10 in A-Flat Major, Op. 32, No. 2: Lento.

CD2:

Frédéric CHOPIN: Nocturne No. 11 in G Minor, Op. 37, No. 1: Andante sostenuto – Nocturne No. 12 in G major, Op. 37, No. 2: Andantino – Nocturne No. 13 in C Minor, Op. 48, No. 1: Lento – Nocturne No. 14 in F-Sharp Minor, Op. 48, No. 2: Andantino – Nocturne No. 15 in F Minor, Op. 55, No. 1: Andante – Nocturne No. 16 in E-Flat Major, Op. 55, No. 2: Lento sostenuto – Nocturne No. 17 in B Major, Op. 62, No. 1: Andante – Nocturne No. 18 in E Major, Op. 62, No. 2: Lento – Nocturne No. 19 in E Minor, Op. posth. 72, No. 1: Andante – Nocturne No. 20 in C-Sharp Minor, Op. posth.: Lento con gran espressione – Nocturne No. 21 in C Minor, Op. posth..

Aldo Ciccolini, Piano Wikipedia

Imitating the art of singing…

Nocturne… Notturno… Nachtstück… are perfect synonyms for “serenade,” “divertissement,” or other concert pieces. At least, this was the meaning given to the word “nocturne” when Verdi was alive. Furthermore, well before Chopin, this “nocturne” was a form intended for wind instruments, in particular horns, and sometimes strings. What, then, was the strange destiny of this word, “captured” for the first time on the keyboard by an Irishman, John Field, a talented but underrated musician (Dublin, 1782 – Moscow, 1837), and which was definitely adopted for the piano by the genius of Frédéric Chopin?

For if we call to mind the form of the Nocturne, it is as indistinct as the musical spirit of the work. The content is like the container: indistinct, dreamy, melancholic, as if composers hesitated to give a more literary name to a form of musical expression that corresponded ideally to the mood of Romanticism, then at its height. Chopin’s Nocturnes fill the night and let our thoughts whirl “in the night air.” The words, said and unsaid, the meaningful silences reflect the loneliness of the musician whose art merges with that of the performer. Chopin sings for himself with a “voice” that is recognizable from the first note: he admits to being in love with bel canto. His touch expresses this passion. The human voice, carried by the right hand, impedes the accompaniment. The performer, therefore, has to evaluate the differences in tempo in the bar, in the phrase, even in the syllables we think we can hear. The absolute autonomy of the two hands, which sometimes fight each other in the syncopation, thwarted by the infinitesimal control of the pedal, gives each interpretation its full value. The phrase remains suspended—an elevation all the more dangerous for the performer, given that the tempo is measured.

“Nocturne” doesn’t mean lack of precision or dilettantism either. Scriabin, Debussy, Fauré, Ravel, and Rachmaninov, among others, use the term, but their writing, like Chopin’s, doesn’t tolerate any approximation.

Poor pianists… With Chopin, they have to create expectation—the desire for the note and the chord that will harmonically resolve the phrasing of the line. Silence then takes on enormous importance.

We will never know if these Nocturnes, masterpieces of the genre, are “easy” or “difficult.” Of course, the C minor in Opus 48 No. 1 is frightening because of its impressive technique. But the debate is elsewhere. Chopin admits it himself: you can sing, or you can’t!

“Indistinct form,” we wrote above… In fact, Chopin’s Nocturne is made up of three parts, the middle one contrasting with the other two. Chopin certainly doesn’t try to innovate. What’s more, the counterpoint is sometimes very severe. You have to look elsewhere—in the ornamentation, which gives fullness to the sound. It is the foundation of a stylized Polish soul, although it would be illusory to try to decipher it in the twenty-one scores. The ornamentation and the declamation relieve the stiffness of the notes.

The rubato, the touch on the keyboard, becomes the signature of the work, as if Chopin were expressing the lyrical piece he never gave us. From 1827 to 1846, all his work is punctuated by Nocturnes and Mazurkas, as if it were a discreet itinerary in a diary.

- Categories

- Composers

- Interprets

- Booklet