Extraits / Excerpts

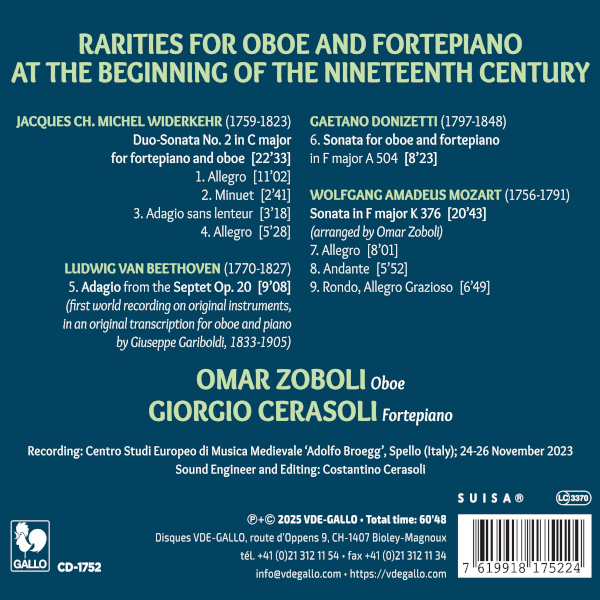

Widerkehr: Duo Sonata No. 2 in C Major - Beethoven: Septet, Op. 20: Adagio - Donizetti: Oboe Sonata in F Major - Mozart: Sonata in F Major, K. 376 - Omar Zoboli, Oboe - Giorgio Cerasoli, Fortepiano

Jacques WIDERKEHR: Duo Sonata No. 2 in C Major: I. Allegro – II. Minuet – III. Adagio sans lenteur – IV. Allegro – Ludwig van BEETHOVEN: Septet in E-Flat Major, Op. 20: II. Adagio cantabile (Arr. for Oboe and Piano By Giuseppe Gariboldi) – Gaetano DONIZETTI: Oboe Sonata in F Major, A 504 – Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART: Violin Sonata in F Major, K. 376 (Arr. for Oboe By Omar Zoboli): I. Allegro – II. Andante – III. Rondo, Allegro Grazioso.

Omar Zoboli, Oboe https://www.omarzoboli.ch/

Giorgio Cerasoli, Fortepiano www.giorgiocerasoli.it

Jacques Widerkehr (1759–1823)

Jacques Widerkehr (1759–1823), an Alsatian composer of the Classical period, distinguished himself through his highly refined chamber music works. The Duo Sonata No. 2 in C major for oboe and basso continuo, performed here by Omar Zoboli, reveals the full subtlety of his writing, balancing formal rigor with graceful charm. Influenced by Viennese masters such as Haydn, Widerkehr developed a distinctive musical language in which the oboe engages in elegant dialogue within a typically French style.

And an oboe appeared in Beethoven’s parlor

Did the oboe really make an appearance in Beethoven’s drawing room? It certainly regularly entered the rooms where the German musician created his compositions. Ludwig van Beethoven, in addition to reserving for the reed instrument a prominent place in his orchestral works (it would suffice to recall the solos at the beginning of the Funeral March, in the Eroica Symphony, and at the reprise of the first half of the famous Fifth Symphony), wanted it among the protagonists in several of his chamber compositions: from the Quintet for piano and wind instruments to the Trio op. 87 (where two oboes converse with an English horn), and the extraordinary Octet Op. 103. Probably for both the aforementioned Trio Op. 87 and the Variations on a Theme from Mozart’s “Don Giovanni” WoO 28 Beethoven had in mind the brothers Johann, Franz and Philipp Teimer, celebrated Bohemian performers whose long activity came to an end in 1796, the year in which Johann and Franz, almost certainly the oboists in the trio, died.

Chamber music in the domestic salon

But let us return to the drawing room to recall how chamber music production was designed—still in Beethoven’s time—predominantly for domestic performances, precisely in those drawing rooms of the aristocracy and upper middle class that, throughout Europe, hosted performances reserved for residents and their guests. For theaters and concert halls, in fact, programs intended for orchestral ensembles were basically reserved. The repertoire that circulated in European salons, clearly different depending on whether one was, for example, in Vienna, Paris or Bohemia, was extraordinarily broad. With the possibility therefore of encountering a vast array of composers who are less well known today but who drew on the same musical language used by the most celebrated musicians, namely Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven.

Let a gastronomic comparison be illuminating: the wealth of ingredients used was entirely shared by a large number of cooks, each of whom then developed recipes according to his or her own taste and inventiveness. That is why even the works of musicians such as, for example, Jacques Christian Michel Widerkehr (1759–1823), to whom we shall return later, Friedrich Theodor Fröhlich (1803–1836) or Carl Anton Philipp Braun (1788–1835) not infrequently contain passages, harmonic solutions, stylistic traits that may be recognizable to those familiar with the classical style of the better-known triad. At that point it is not a question of finding out who copied and who was copied, because each artist had as a reference the same musical vocabulary used not only by Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven but also by many other colleagues.

Widerkehr and echoes of Beethoven

It will come as no surprise, then, that the same first two harmonies with which Beethoven’s First Symphony opens are found at the beginning of the second of Jacques Widerkehr’s Trois Duos pour piano et violon ou hautbois, composed around 1794 and published by Érard in 1817. Born in Strasbourg, possibly a pupil of Franz Xavier Richter, the Frenchman, thanks to his cello studies, played regularly in Paris from 1783 with the Orchestra of the Olympic Lodge and that of the Spiritual Concerts but without being permanently on the staff. His main activities, until the Revolution, therefore seem to be music teaching and composition. It is the fashion for concertante symphonies that allows Widerkehr to know celebrity: during the Revolution and the Consulate his name appears frequently in concert programs.

The solo parts of many of the pieces of which he is the author are written first and foremost for wind instruments (clarinet, flute, oboe, bassoon or horn) and are intended for the early musicians of Paris. Like these concertante symphonies, considered among the best in circulation at the time throughout Europe, his chamber music reveals a luminous style, accurate in detail and rich in the combination of harmonic effects. These characteristics are also found in the Deuxième Duo pour piano et violon ou hautbois, in C major and articulated in four movements, where the classical sonata generally contains only three: two allegros (the first of which is in sonata form and the second en rondeau) frame a brilliant minuet, by then very close to the scherzo found in symphonies, and then a slow movement, particularly expressive.

- Categories

- Composers

- Interprets

- Booklet