Extraits / Excerpts

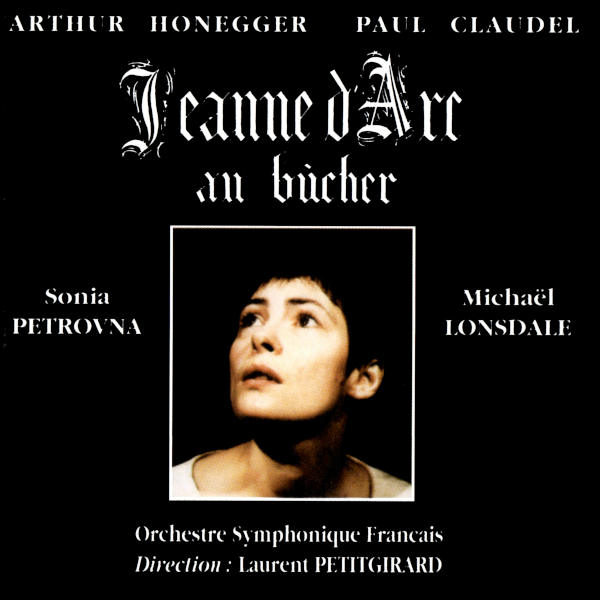

Arthur Honegger / Paul Claudel: Joan of Arc at the stake - Sonia Petrovna - Michaël Lonsdale - Orchestre Symphonique Français, Laurent Petitgirard

Arthur HONEGGER / Paul CLAUDEL: Joan of Arc at the stake

Jeanne d’Arc au bûcher: Prologue – Scène 1: Les voix du ciel – Scène 2: Le livre – Scène 3: Les voix de la terre – Scène 4: Jeanne livrée aux bêtes – Scène 5: Jeanne au poteau – Scène 6: Les Rois ou l’invention du jeu de cartes – Scène 7: Catherine et Marguerite – Scène 8: Le Roi qui va-t-a Reims – Scène 9: L’épée de Jeanne – Scène 10: Trimazô – Scène 11: Jeanne d’Arc en Flammes.

Sonia Petrovna, Jeanne

Michaël Lonsdale, Frère Dominique

Christian Papis, Porcus

Anne-Marie Blanzat, La Vierge, La Mort

Claudine Le Coz, Marguerite

Constance Fee, Catherine

Jacques Schwarz, Un Héraut, un clerc

Michel Fockenoy, Un Héraut, un clerc

Compagnie du Théâtre de la Pie Rouge: Sylvie Habault, Guy Faucon, Jean-Pierre Bourdaleix, Joël Lefrançois, Jean-Claude Duboc.

Orchestre Symphonique Français, Chœur de Rouen-Haute-Normandie, Maitrise des Hauts-de-Seine,

Laurent Petitgirard, Conductor.

Joan of Arc at the stake

The meeting of Paul CLAUDEL and Arthur HONEGGER is one of those events that give an era its color.

The great Catholic poet and the Protestant composer almost did not collaborate together. Indeed, when CLAUDEL was asked to write the libretto of this JEANNE D’ARC, he refused categorically: “Joan of Arc is an official heroine, who has spoken, and whose words, in all memories, cannot undergo too free a transcription. It is difficult to form a historical character in a fictional setting,” the poet explained, adding prettily, “Do we gild the gold and bleach the lilies?”

But fortunately, taking the train again the day after this refusal, CLAUDEL had a vision: while allowing himself to be hypnotized by the abstract scrolling of telegraph poles along the track, he saw two hands knotted, joined, making a cross that he himself interpreted as “All the hands of France in a single hand, such a hand that it will no longer be divided.”

Fifteen days later, he read his manuscript to HONEGGER.[show_more more=”Show More” less=”Show Less”]

It is at once much more than a libretto which appears, but an exalting poem, a poem which inscribes the music in its internal rhythm, in its essence, in its flesh. A poem that uses the scansion of the sentence, the euphonies of the language, but also the oppositions choir/solists as elements of musical architecture.

Moreover, this poem is built according to a form which allows the structuring, according to the cinematographic technique, of the flashback: the stake of Rouen is at the same time departure and result of the work, as if Jeanne, at the moment of her death, saw her life again, as, it is said, the dying people feel it at the ultimate moment.

Finally, CLAUDEL’s text is already, even before the first note is struck, a braiding of colors that ensures a fantastic dynamic with all these levels of language, from the grandiose to the truculent, from the mystical to the popular, from the sublime to the grasseyant, from “The pages of night, of Blood, of overseas and of crimson have been stripped away under my fingers and only a golden initial remains on the virginal parchment” to “Heurtebise, mon compère, t’as retrouvé ta commère” (Heurtebise, my friend, you’re back to your gossip girl)… Harry HALBREICH, in his fascinating biography of HONEGGER, sums it up very precisely by explaining that, in this cathedral of words, CLAUDEL makes “the capital and the gargoyle live together”.

HONEGGER immediately threw himself into his work, captivated by the poet’s text, and, after having completed a few commissioned works, was able to finish his JEANNE at the end of 1935.

It is however only on May 12, 1938, following Joan of Arc at the stake

The meeting of Paul CLAUDEL and Arthur HONEGGER is one of those events that give an era its color.

The great Catholic poet and the Protestant composer almost did not collaborate together. Indeed, when CLAUDEL was offered to write the libretto of this JEANNE D’ARC, he refused categorically: “Joan of Arc is an official heroine, who has spoken, and whose words, in all memories, cannot undergo too free a transcription. It is difficult to form a historical character in a fictional setting,” the poet explained, adding prettily, “Do we gild the gold and bleach the lilies?”

But fortunately, taking the train again the day after this refusal, CLAUDEL had a vision: while allowing himself to be hypnotized by the abstract scrolling of telegraph poles along the track, he saw two hands knotted, joined, making a cross that he himself interpreted as “All the hands of France in a single hand, such a hand that it will no longer be divided.”

Fifteen days later, he read his manuscript to HONEGGER.

It is at once much more than a libretto which appears, but an exalting poem, a poem which inscribes the music in its internal rhythm, in its essence, in its flesh. A poem that uses the scansion of the sentence, the euphonies of the language, but also the oppositions choir/solists as elements of musical architecture.

Moreover, this poem is built according to a form which allows the structuring, according to the cinematographic technique, of the flashback: the stake of Rouen is at the same time departure and result of the work, as if Jeanne, at the moment of her death, saw her life again, as, it is said, the dying people feel it at the ultimate moment.

Finally, CLAUDEL’s text is already, even before the first note is struck, a braiding of colors that ensures a fantastic dynamic with all these levels of language, from the grandiose to the truculent, from the mystical to the popular, from the sublime to the grasseyant, from “The pages of night, of Blood, of overseas and of crimson have been stripped away under my fingers and only a golden initial remains on the virginal parchment” to “Heurtebise, mon compère, t’as retrouvé ta commère” (Heurtebise, my friend, you’re back to your gossip girl)… Harry HALBREICH, in his fascinating biography of HONEGGER, sums it up very precisely by explaining that, in this cathedral of words, CLAUDEL makes “the capital and the gargoyle neighbor”.

HONEGGER immediately throws himself into the work, with the subaltern difficulties that this Joan of Arc will be created in Basel, under the direction of Paul SACHER, with Ida RUBINSTEIN in the title role, the initiator of the idea and the dedicatee.

The piece is divided into 11 scenes, preceded by a prologue, written later: CLAUDEL, distressed by the dramatic events of the war and the occupation, added it in 1944 to place the work in a contemporary perspective, while preserving its exemplary character and its mythical force.

One of the many original features of this unique work is the skilful balance between the spoken and sung voices, the choirs and the orchestra: the title role, in particular, is entrusted to a spoken voice, but very much framed musically, with passages in which Jeanne’s voice is noted in its rhythmic inflections, and others in which she invents her own rhythm, in the movement of the work and the performance.

This shows how much an exceptional interpreter is needed for this role, an actress but above all a speaker, possessing within herself this musical pulsation and this natural apprehension of rhythm which is the very basis of the poem. Ida RUBINSTEIN must have had all these qualities. Sonia PETROVNA, today, is endowed with this same inner strength, this same intensity which, from the very first words (“who is calling me?”), as if coming out of a dream, imposes itself absolutely. She brings this Jeanne to an altitude of overwhelming truth because without any effect, without ostentation, without shouting, simple nakedness of a voice without tension which confers, in view, to this music something of burning.

Laurent PETITGIRARD, with his French Symphony Orchestra, has precisely known how to give this music both its brilliance and its contrasts, the suppleness of its fades and the sharpness of its breaks.

He also insisted on ensuring the exact orchestral color wanted by HONEGGER with the three saxophones replacing the three horns, the absence of harp but the presence of two pianos which, in the scene of the Game of Cards, are transformed into harpsichords by means of a curtain rod placed on the strings; with also the ondes Martenot, for which HONEGGER had a predilection, and which play here their role of more or less strange, secret evocation, like that of the dog which howls in the night.

With Michael LONSDALE’s massive and anguished Brother Dominique, the Shakespearian greenness of the popular scenes, with their affirmed truculence, whether sung (Porcus) or spoken, This version of Joan of Arc at the stake is an important milestone in the history of CLAUDEL-HONNEGGER’s masterpiece, since its first recording made in 1943 in the Pathé-Marconi studios, under the direction of Louis DE VOCHT, with Marthe DUGARD as Joan and Raymond GEROME as Frère Dominique

Joan of Arc at the stake is a unique work: dramatic oratorio, of course, as its subtitle states, but also a “ballad” in the medieval sense, a naive fresco and a concerted metaphor, a deployment of many of the potentialities of the spoken voice in a dialogue with the musical, orchestral or choral masses. Modern in its form and classical in its language, but also classical in its spiritual power and modern in its dizzying anxiety, in its sense of the absurd and of the plural, in its mixture of genres, in fact, unclassifiable as are all works that go beyond the occasion, Joan of Arc at the stake is, with its grotesque facets and its bursts of emotion, its creaks and upheavals, a superb reflection of life. This recording bears witness to this.

Alain DUAULT

[/show_more]

- Categories

- Composers

- Interprets

- Booklet