Extraits / Excerpts

Gustav Mahler: Das Lied von der Erde - Hedwig Fassbender, James Wagner - Ensemble Contrechamps, Armin Jordan

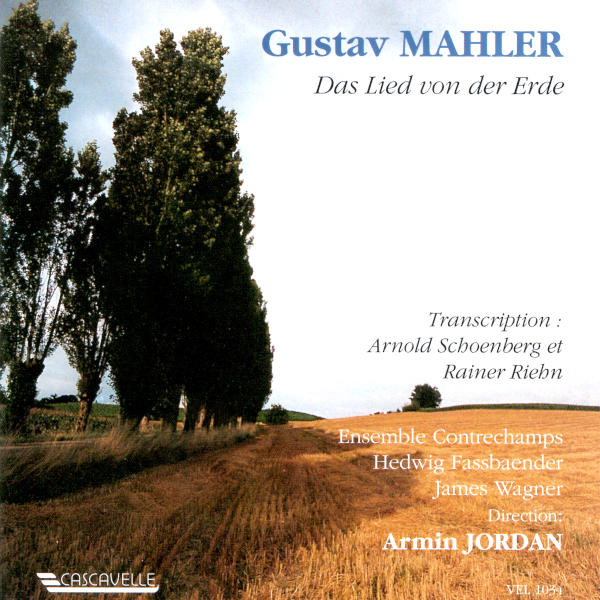

Gustav MAHLER: Das Lied von der Erde

Das Lied von der Erde: I. Das Trinklied vom Jammer der Erde – Das Lied von der Erde: II. Der Einsame im Herbst – Das Lied von der Erde: III. Von der Jugend – Das Lied von der Erde: IV. Von der Schönheit – Das Lied von der Erde: V. Der Trunkene im Frühling – Das Lied von der Erde: VI. Der Abschied.

Hedwig Fassbender, Mezzo-Soprano – James Wagner, Tenor – Ensemble Contrechamps, Armin Jordan, Conductor.

Gustav Mahler: Das Lied von der Erde (The Song of the Earth), transcription by Arnold Schoenberg and Rainer Riehn

In autumn 1921, Arnold Schoenberg made a start on arranging Gustav Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde (1907-1908) for a chamber orchestra. The piece was intended to be played at concerts organized by the «Verein für musikalische Privataufführungen» (the Society for Private Musical Performances) which Schoenberg had founded in 1918 in Vienna to present a wide range of contemporary music better known in properly rehearsed performances. The Society wanted to break away from conservative attitudes and the dull routine of official musical life which Mahler had already criticized and battled against while he was Director of the Vienna State Opera. It also wanted to counter the weight of prejudice and press criticism at the same time as filling a void in Vienna’s musical life.

Earlier in 1921, Schoenberg had already adapted Mahler’s Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, dating from 1884-1885, for a small ensemble and this piece had been performed at the 43rd Concert given by the Society. It is of significance that Schoenberg had been drawn to these two works by Mahler which date from either end of the composer’s life-work and have the strongest Jewish flavor to them. Schoenberg himself had been seeking to return to his own religious roots (after converting to Protestantism at the age of 18) against a background of mounting anti-Semitism. In these two works of Mahler, the romantic figure of the «Wanderer» is a thin disguise for the Wandering Jew. The Earth in question in the songs glorifies neither the homeland nor the soil from which the Nazi mythology was to spring forth, but rather focuses on the place where it is difficult to set down roots, a place of anguish and alienation: the inaccessible land, the lost land. These themes already permeated Schoenberg’s work. It is not inconceivable that the author who composed Die Jakobsleiter perceived Mahler’s work to be an outward expression of his own malaise and sense of confusion: in summer 1921 – six months after his work on the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen and six months prior to the work on the Lied von der Erde – Schoenberg was turned back from the region around Salzburg where he usually spent his holidays on the grounds that he was Jewish and that Jews were no longer welcome. The two distressing and bitter letters that he sent later, in 1923, to his close friend the painter Wassily Kandinsky bear witness to the key significance of this episode in Schoenberg’s life as well as revealing Schoenberg’s lucidity as to the tragic consequences such a rejection was likely to have.

[show_more more=”Show More” less=”Show Less”]

The transcription of the Lied von der Erde was never finished. Schoenberg committed to paper the principles underlying the arrangement on the cover page of the orchestral score, before going on to transcribe, on the same score, up to bar 178 of the first song. Within Schoenberg’s circle, rescoring and transcription work, like the rehearsals for the concerts, were regarded as being collective activities so it is feasible that Schoenberg was preparing the work for an assistant. The prospectus for November 1921 announced that the work featured on the concert program for the following season in a transcription by Webern, but no trace of this work has ever been tracked down. Abandonment of the project can undoubtedly be blamed on the fact that the Society was forced to cease its activities at this time for financial reasons.

The idea of reducing a full-scale orchestral work for a smaller ensemble was still not a common one at the time and had only made a belated appearance in the Society’s work. The Society did, however, produce piano arrangements of symphonies (and particularly Mahler’s which were performed on a regular basis). The principles of adaptation furthered by Schoenberg can be summarized in a comment by Rainer Riehn: «Reduction without loss». The aim was not to rethink the original piece and to reformulate it in another way, as Busoni did with one of Schoenberg’s own piano pieces (without altogether impressing the composer), but rather to go to the heart of the musical thinking and reveal the musical and spiritual core of the work. By pinpointing the individual voices amid the massed sounds of the full orchestra, Schoenberg laid stress on their structural function and their strength of expression, in keeping with those very same demands that he imposed upon himself as a composer. However, at the same time, he reinforced an underlying pattern in Mahler’s own music, particularly evident from the Kindertotenlieder and Fifth Symphony onwards: the quest for instrumental writing that highlights polyphonic structures and which, through the use of combinations of instruments at times similar to those found in chamber music (the opening of the Kindertotenlieder for instance), cuts out the rather seductive, but nevertheless superficial, effects of the grand orchestra. Mahler’s writing, through its discipline, turns away from the easy attractions of imitation and seeks to foster an aesthetic appeal based on a notion of distance: thus sentimentality in Mahler’s work, like marches or country-dances, is never allowed to dominate in the foreground. The virtuoso handling of the orchestra, based on the evocative spell cast by the mass and volume of sound, gives way to the sparse textures of musical construction and inner expression.

Schoenberg retained the original distribution of the instruments in keeping with the notion that the same colors and combinations of tones should be preserved in the reduced format. The main lines of music should be allocated to the same instruments, with the harmonium and piano taking the secondary voices and filling in for those instruments that were missing. The harmonium, therefore, replaces the second wind instruments, with the piano playing certain solo phrases, such as the trumpet or harp, the two instruments complete the harmonies. This configuration tends to produce the best reconstruction possible, but the piano can pose a problem: its merging with the overall tone of the ensemble playing depends heavily on the qualities of the pianist. Reducing the orchestral score also brought into focus another feature of Mahler’s writing which is often overshadowed by the sheer weight of the orchestral sound: the absence of the bass as the basis of harmony and rhythm. As a result, melodic lines are interwoven freely in tonality and modality, producing counterpoint that is far from academic. The highly chiseled nature of the lines in all voices is accentuated by the timbre of the solos and the woodwind section’s relative importance to the strings. Attempting to arrange the piece for a chamber ensemble, to a certain extent, involves analyzing the original work. It pulls Mahler’s orchestra towards the sparseness characteristic of work of the Second Viennese School, typified in compositions dating from Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony Op. 9 (1906) to works written by the «Three Viennese» (Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern) in the early 1920s. The arrangement reveals, more boldly than the original piece, the archaic character of the tones and musical snatches drawn from the world of childhood and the associated nostalgia.

The relationship between Schoenberg and Mahler was founded on solidarity, friendship, and admiration. Mahler had bravely supported Schoenberg when he was ostracized by the Vienna establishment, especially during the riotous concerts when his works so scandalized audiences. He gave him financial aid on several occasions. Schoenberg, for his part, dedicated his Harmonielehre («Theory of Harmony»; 1911) to Mahler’s memory and defended his music with staunch devotion until his own death. Alma reports that Mahler, on his death-bed, was still thinking of the one person whom he considered to be his genuine spiritual heir: «If I go, he will have nobody left».

Rainer Riehn took Schoenberg’s work in its rough-hewn state, completed the score while keeping faith with the composer’s ideas, and solved the many problems that arose by referring back to and studying Schoenberg’s work, particularly his earlier transcription of the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen. In all respects, he remained scrupulous in keeping true to Schoenberg’s intentions. The work was first performed in its reduced form in July 1982 under the direction of Rainer Riehn himself during the second Toblach Music Festival.

Philippe Albèra, transl. K. Watson

[/show_more]

- Categories

- Composers

- Interprets

- Booklet